What You Bring To the Reading Room

Last time out, the trivia question was: Stanley G Weinbaum was known for his

inventiveness and, at the time, solid science in his fiction. Today's SF, of

course, runs the gamut between what is really fantasy and hard science

fiction typified by such writers as Asimov, Brin, and Bedford (to stick to

the beginning of the alphabet). One hard SF writer in particular, who's been

at it for nearly forty years, has built an extensive universe and populated

it with entirely believable critters and peoples. Who is the creator of the

following species: Pak, Trinocs, and Outsiders (which has nothing to

do with HP Lovecraft, bear in mind)?

And the answer is, Larry Niven. This is something of a gimme for true SF

fans, Iíd think. Larry Niven has been a stalwart figure in the SF field

since he first appeared in Galaxy and If

magazines. Early in his career, he decided that some of the hard background

work he did for his SF stories shouldnít go to waste and began to build a

universe of his own, prosaically called of course, Known Space. It is

indeed a rich and detailed universe and heís still writing stories in

itóincluding the newly released Ringworld Children [Footnote

1]. I left out the Kzinti from the lists, as well as puppeteers since I thought they made it too absurdly easy. The species mentioned above are as

follows:

Pak: The progenitors of humanity in ALL itís form, the Pak

come from a world very much closer to the center of the galaxy and exist in

three stages, infants/children, breeders, & protectors. The protectors are

super-intelligent modifications of the original somewhat human form,

dedicated by evolution and a weird virus to the protection of their own

progeny. They ended up building Ringworld.

Trinocs: A young race of beings, very touchy about a lot of

things and not greatly detailed in the Niven books. But they see by radar

and one at least, is a great artist. See the Beowulf Schaefer stories.

Outsiders: A very strange race of critters that are

bases on a completely different biochemistry than any of the other species

in Nivenís Known Space. They developed in an extremely cold

environment where liquid helium is cold enough to exhibit strange

properties. They also are the original inventors of the hyperdrive, which

they sold to humanity for a huge sum of money. They have a weird fixation

with a strange space-going plant that migrates from the galactic core to the

extreme ends of the galactic arms, and back again. No one knows why and the

fee they would charge to explain is more than the worth of Known

Space.

If youíre not a Niven fan, you should be. Rich, rich imagination and solid

writing. No more needs to be said.

* * * *

This time out is going to be different, again. Possibly even weird. So, sit

back and see if you can follow a particularly weird thread that all starts

with Roger Zelazny.

Iíve been a fan of Roger Zelazny for a long time, though I find I prefer his

earlier works to his later ones. In point of fact, my favorite Zelazny title

is This Immortal (aka And Call Me Conrad), which

won a Hugo. It originally was published in Fantasy & Science

Fiction and then slightly expanded and published by Ace. There was

no early hardback version.

Back in the very early 80ís, I chanced to stumble across the Greg Press

series of books, a very nice, understated (and somewhat underappreciated)

series that didnít have dust jackets and was uniformly bound in a sharp

looking dark gray with silver lettering. I ended up buying some L. Ron

Hubbard (Final Blackout) as well as their printing of

This Immortal. It was nice, finally, to have a hardback

version of it.

I was short of money (as all young married people seem to be, barring of

course preppies from oil rich parents in Texas), and couldnít afford many

books for the rest of the 80ís and consequently missed out on the beginning

of a great series of books by Easton Press. Easton Press is kind of a classy

book club company that specializes in not specializing. They do the

classics, they do contemporary, they do just about everything one can think

of, but all of the titles are well done. Think of them as the top of the

book club chain and you wonít be far off the mark.

They brought a new series in the 1980ís called The Science Fiction

Classics that ranged from early classics to newer ones to some that

were, when first published by them, new indeed. They attempted (and

accomplished to my mind) to be representative of the entire Science Fiction

field, from the beginning to the present. They didnít concentrate on a

single author or style (New Wave vs. Hard SF vs. whatever). Iíve wondered

how they decide which book to include and which book to omit, but from

looking at the list, I canít even begin to guess.

I just picked up a copy of Zelaznyís This Immortal and itís a

beautiful example of the art of book binding and printing. No dust jacket,

however. None of the Easton Press titles have a dust jacket because they are

showcasing the art of bookbinding.

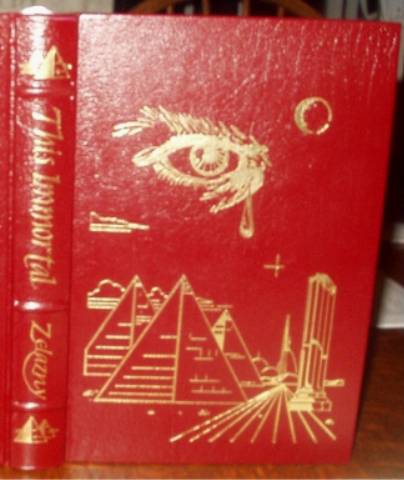

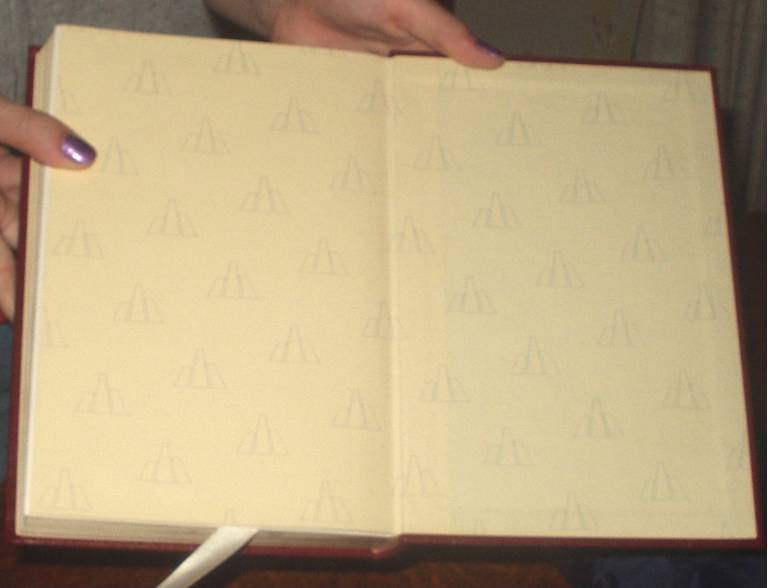

This Immortal is bound in a deep maroon leather with gold

embossing on the face, back and spine. For the Zelazny title, they had some

Egyptian theme designs on the face and back (part of the novel takes place

in Egypt), as well as interior ink illustrations. The paper is beautiful.

The book even sports an attached ribbon for marking oneís place, much like

one finds in truly classic books or the Bible. The trimmed pages are

tipped with gold. Price was fairly cheap, considering: $45.00 (and yes, it

was a used book, but used by a collector. Itís virtually spotless).

Now, hereís the crux of this column. Is such a book collectable?

Remember, this particular book is really nothing more than the output of a

very expense book club. Very classy, perhaps, but still tarred with the same

brush as The Franklin Mint issues of coins. Are they on a par with

books Iíve mentioned in past columns that really are published strictly for

the collectorís market? Perhaps.

I ran into another book that falls roughly into what Iíve more or less

termed collectorís market books (Wandering Star in England and much of the

Don Grant books, these days), by Mike Resnick, called

Adventure and exchanged a couple of emails with Mike about the

book. There are two versions of the book that were published. The first has

a faux leather binding and appears to be a nicely bound and printed book

from the images Iíve seen. But the second version only had a grand total of

twenty-six (yes, 26) copies printed and bound, each assigned one letter of

the alphabet and inscribed by Mike. I asked him about the books and for his

thoughts on book collecting.

Mikeís a professional writer, first, last and always [Footnote 2]. His

response was more or less that he didnít. Think about book collecting. For

him, itís kind of a null topic. He merely wants to continue writing fine

fiction (non-fiction as well, for that matter) and stretching himself as a

writer. Book collecting? Why would he want to spend time thinking about

that?

I honestly couldnít give him a legitimate reason since there probably is no

one solid reason why book collecting can be called a good thing.

Except to note this: The great libraries of the world were more or less

assembled with the idea of collecting books [Footnote 3]. There

is a purpose to it all: Preserving the knowledge, thoughts, dreams and

experiences of the human race. Along the way, books themselves occasionally

became works of art and the contents of them mattered a bit less -- but I

defy anyone to point to a book that is both a work of art and filled with

blank, empty pages. Sure, people buy blank books for journals and what-not,

but theyíre not what Iím talking about. Books that are beautiful and exhibit

the best of the binding art all have something inside of them, at the core,

that invited the passion of someone else. Thatís why people become

rabid Robert E. Howard collectors, or collectors of H. P. Lovecraft or L.

Frank Baum or any legion of other writers. Why, for example, I have copies

of books by Mike Resnick, and they sit side by side with other books that

individually and collectively, mean a great deal to me.

So, the question is thus answered, albeit by a curved and idiosyncratic line

of reasoning. Yes, the Easton Press copy of This Immortal

is a collectable book. Because of what I, personally, bring to the

book. The book is more than the contents. It is more than the art displayed

in the binding. Itís what I, personally, bring to the book and take away

with me when I put it back on the shelf. Itís the effect of the words Iíve

read, the images Iíve imagined and the stories Iíve lived in the reading of

the book. You bet itís collectable.

I warned you this was going to be a weird column, didnít I?

Trivia Question:

The years 1965 and 1966 were huge for Zelazny, when it came to

awards.

Hereís a quick list of the nominations and award Zelazny earned during 1965

and 1966.

Hugo Nomination: ďThe Doors of His Face, the Lamps of His MouthĒ, best

novelette (1965).

Hugo Award: This Immortal (1966).

Nebula Award: ďHe Who ShapesĒ, novella (1965), ďThe Doors of his Face, the

Lamps of His MouthĒ, novelette (1965),

One other writer was just breaking into the field at that time and went up

against Zelazny for a number of the awards above. Who was that writer and

what awards did he win? The answer of course, will be next time.

* * * *

Footnote 1: Just out recently. Itís published by Tor, ISBN

0-765-30167-9, $24.95, 284 pp. There is a review in this issue of DMR.

Return

Footnote 2: Which is why he is so patient with email from weird people he

doesnít know or at least, doesnít know very well. He strikes me as having a

huge store of patience . . . .

Return

Footnote 3: All right, manuscripts to be more accurate about the great

libraries of antiquity.

Return

Return to the Table of Contents

Reviews Updated for 2009! | Issues 2001-2004 | Links | About DMR | Home